Isn't it uncanny how the authors we sometimes just happen to be reading in tandem together collide out of the blue outside of what we're reading and we discover, without any prior knowledge, that the writer's lives, beyond their fiction, poetry, and literary criticism, intersected intimately? Leaves me wondering aloud if sometimes what we've chosen to read, being the lifelong passionate readers we are, was somehow nudged in one way or another by the books themselves upon our shelves and nightstands? Before anybody scoffs or labels me nuts (and for the skeptics, I'll grant you, in a spirit of magnanimity offered in the hopes you'll continue reading, that I'm nutty) keep in mind that William H. Gass, a titan of Literature and Philosophy among post-1960 Artist-Thinkers of the Earth, conceptualized the animate possibilities of books in an essay "The Book as a Container of Consciousness" that he began as an address to a "conference on the book," hosted by the J. Paul Getty Center, and later polished up for publication in his 1996 essay collection Finding A Form. Theoretically, therefore, books could in fact be in possession of their own "minds" so to speak; and having minds, couldn't they vie for our attentions, and perhaps mysteriously attract our attention to specific spines on our bookshelves?

After reading the first sentence of The Accident, I had the impulse to rush here and quote it, but I kept reading. Then I had the impulse to quote the first paragraph, the first page, the entire first chapter, but I had to keep reading. Over halfway through this slim novel, I still wanted to quote every word of it, but how absurd and impractical would that be? Instead, I'll honor my first impulses and quote the first sentence, the first paragraph. . . .

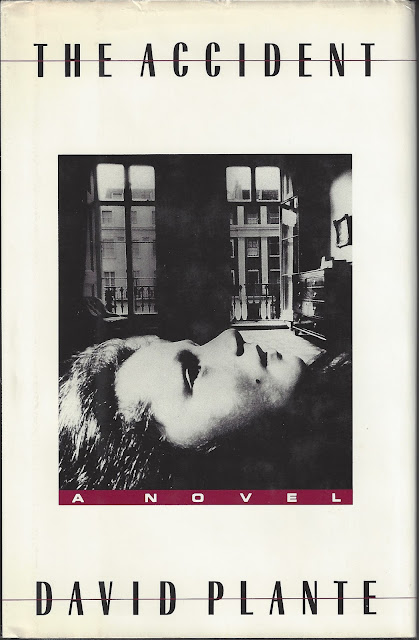

"WALKING ALONG the Seine, close to the swiftly moving but heavy water that slithered against the quai, walking round the couples sitting at the edge with their arms about each other, one young man with his hand inside the unbuttoned blouse of the young woman and holding her breast, I longed for what I felt couldn't be fulfilled even by making love, only by throwing myself into the river, not to die, but to be taken somewhere else on its current, which, out at the center, streamed in smooth, shining, infolding waves."The Accident is a distillation of language; it's a short novel that's been aged long. That the sentences go down smooth in "shining, infolding waves" isn't to say they lack a complex of flavors because their finish lingers. The Accident examines in deep psychological detail the consequences of faith and its opposites atheism and nihilism over the course of a semester in the 1950s at the Université catholique de Louvain in Belgium, in the lives — and in the ruins — of four students from the States: Tom Domlon, Karen, Vincent, and an unnamed narrator. It is the unnamed narrator's austere, philosophical rumination from his unspecified future vantage, looking back at what he lost and also learned from the wreckage, that moves the psychological action along.

In critiquing "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," Stephen Spender describes the "failure" of Prufrock, "for which he despises himself, is failure to relate either with another person or with the Absolute. He is isolated, he cannot communicate". And the same could be said of David Plante's unnamed narrator — a conflicted self-loather mad at himself for once believing and now for his unbelief, and unnamed, perhaps, to emphasize not only his lack of identity but his rejection of any identity, Catholic or otherwise, he could have claimed — who likewise, surrounded by his classmates almost desperate to know him, who in fact go out of there way to engage him, cannot — no, he will not — open his tortured heart to them, until it is too late. Spender wrote of Prufrock that he was "superior to the inhabitants of his world because he is conscious of being inferior," which again, describes (and the similarities between the two characters are uncanny to the point I can't help but wonder if Plante purposely fashioned his narrator after Eliot's Prufrock) the convoluted, paradoxical psychology, of David Plante's No-Name narrator in his torn, tugging desires that, in turns, make him in one moment want to belong with his college comrades, and the next remain apart, alienated.

What follows is the Reaper's abrupt arrival in a blinding light on an otherwise starry tranquil night in the French countryside near Paris, where finally, we understand, as the dramatic yet understated tension that David Plante, in his enchanting poetic prose, has built and built and built toward its climactic crash, why he titled his beautiful brilliant novel as he did. Where faith and fatalism collide, there's going to be a terrible accident.

Comments

Post a Comment